Sunday, June 28, 2015

INDEXING THE FREEDMEN'S BUREAU RECORDS

I've now spent most of a day online indexing Freedmen's (sic) Bureau Labor Contracts, Indentures, and Apprenticeship Records, 1865-1872, for their eventual searchability via FamilySearch, a Mormon genealogical service. Last night I very much needed to talk over with Margot the impact this is having on me.

This particular project is far more difficult, for a number of reasons, than the 1940 census indexing push I participated in last year. To begin with, the records are older, images more decayed, paleography more antiquated, though all familiar enough to me after decades of studying primary source documents back to the 1600s. However, there is no "form" being filled in here. Each contract is a handwritten, freely worded entry in a log book, the wording not exactly the same twice, in diverse handwritings. Even the simple main details to be indexed -- date, location, names of contractor and contractee -- often require much poring over and guesswork to be determined.

The non-indexed portions are where the human story lies, drawing me in to read the whole thing. Most of what I indexed was from three counties in Virginia -- Accomack, Dinwiddie, and Danville (an independent city). These regions are diverse from each other, and will be strikingly different from, say, contracts created in Mississippi or Alabama. It is too early for me to suss out these geographic/cultural differences.

Maybe half of the contracts involve a newly freed person who is female, which seems to indicate absolutely everybody in that group had to work to survive. A depressing number of them contract out the labor of children as young as 8 years. There is obviously one quantum leap from emancipation: Families are no longer divided up and sold away from each other. But black children are still not having childhoods.

The wages are impossibly low, subsistence level at best. When it is sharecropping, typically the white landowner is providing only the land (clapped out as it may be), seed, and perhaps a plow and mule or horse for agricultural use only, as well as the right to live in whatever shack was already there. For this they demand, on average, half of all crops produced. If the crop fails, the sharecropper still owes. All planting decisions are under the rigid control of the landowner, and the language spelling this out is both florid and highly authoritarian. ANY resistance to the landowner's dominance will result in the sharecropper being expelled from the land.

This is, as Margot said, serfdom, pure and simple.

But I know that an astoundingly number of these families somehow combine starvation wages and unending labor enough to buy land by a decade later. They donate precious bits of their new land to found schools and churches. They track down and bring back home all family members they can find. They marry and learn to read, they vote in the few years before Reconstruction is sold out by the so-called emancipating North, and they, on their own, keep the South alive as an agricultural player in America.

In these documents, however, a third of them are still listed only by first names. Whether they have not yet chosen surnames (seems to me they would do that even before marrying), or those surnames are deliberately being rejected by the white male record taker, is something to be proved once all these records can be sifted through by those of us whose ancestors they were: African-American history as told by African-Americans.

It hurts, to see this disrespect firsthand. I wish I could make it never have happened. But denial is the addictive comfort of whiteness, and I chose to be a race traitor long ago, to see as much of the truth as I could bear, grieve the barriers to my understanding, and go back for more witnessing. Full humanity demands no less.

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

10:42 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: African-American history, American South. historical research, Freedmen's Bureau Records, personal sharing, slavery

Monday, February 22, 2010

ON WASHINGTON'S ACTUAL BIRTHDAY

First, a link to an interesting historical essay by Acilius at Panther Red, The Labors of Hercules, which begins "George Washington may have been in some ways uniquely admirable as a political leader, but as a slaveholder he was no better than he found it convenient to be."

And, an oldie but goodie, the Washington Rap. NOTE: NOT SAFE FOR WORK OR CHILDREN. Seriously.

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

4:01 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Founding Fathers reality check, George Washington, Panther Red, slavery, Washington Rap

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

DANCING FOR ATONEMENT

Matt Harding has a new "dancing all over the world" video.

I am crying uncontrollably every time I see it. Too many thoughts to chain together coherently...

I notice when the people who join him include no women or girls: That place in the world has us locked down from free expression of our humanity. Too many places like that.

Tonight on PBS I watched Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North. This is a documentary made by Katrina Browne, descendant of the DeWolfs of Bristol, Rhode Island. She, along with nine other members of her close and distant family, confront their legacy as the largest slave-holding dynasty in U.S. history. They "retrace the Triangle Trade and gain a powerful new perspective on the black/white divide."

It's the best film I've seen about the reality of how America's wealth is based on human trafficking and centuries of pathology. As one of the DeWolf cousins eventually comes to say, "It was evil they did, they knew it was evil, and they did it anyway." This is especially true for the North, which controlled slave trade in the U.S. but managed to "buy" their way into no longer being held accountable by claiming they fought the Civil War to end slavery.

The emotional and spiritual process experienced by this family is shown in detail. By the end, they are able to also begin naming their class privilege, and to undertake action of reconciliation and reparation. The African and African-American voices in the film, especially that of co-producer Juanita Brown, also play a serious role in its development.

Do whatever you can to watch this film. See if it is being re-run this week on your own PBS channel. The PBS P.O.V. trailer can be viewed here.

From the website: "The issues the DeWolf descendants are confronted with dramatize questions that apply to the nation as a whole: What, concretely, is the legacy of slavery—for diverse whites, for diverse blacks, for diverse others? Who owes who what for the sins of the fathers of this country? What history do we inherit as individuals and as citizens? How does Northern complicity change the equation? What would repair — spiritual and material — really look like and what would it take?"

Last night I received an e-mail from a very distant cousin who also does genealogy who found our shared lineage posted at RootsWeb. She says there is an error in the pedigree I was given by another researcher, in the Davis line. If she's right, then I am possibly not descended from Captain James Davis of Jamestown, who was one of the first white colonists on this continent and one of the men who in 1619 decided to buy Africans as slaves, the first in America.

I've spent my entire adult life owning my heritage and doing the work of atonement. James Davis has loomed large in that landscape. If he is removed from the picture, I wonder what will shift.

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

1:29 AM

5

comments

![]()

Labels: classim, DeWolf family, history of racism, Juanita Brown, Katrina Browne, Matt Harding, reparations, sexism, slavery, Traces of the Trade

Thursday, June 19, 2008

JUNETEENTH

Happy Juneteenth, ya'all.

Happy Juneteenth, ya'all.

For those of you who are white and/or live in states which do not celebrate it, this is an originally African-American celebration of the date in 1865 when the slaves in Galveston, Texas found out that as of January 1, 1963, they had been freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. The holiday, also known as Freedom Day or Emancipation Day, was for a hundred years celebrated first in Galveston, then in Texas. It is now observed in 26 of the United States.

According to Wikipedia, "Legend has it while standing on the balcony of Galveston’s Ashton Villa, Union General Gordon Granger (backed by 2000 federal troops) read the contents of “General Order No. 3”: (Juneteenth, painting by G. Rose)

(Juneteenth, painting by G. Rose)

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere. (Juneteenth celebration in Austin, Texas on 19 June 1900)

(Juneteenth celebration in Austin, Texas on 19 June 1900)

"Former slaves in Galveston rejoiced in the streets with jubilant celebrations. Juneteenth celebrations began in Texas the following year. Across many parts of Texas, freed people pooled their funds to purchase land specifically for their communities’ increasingly large Juneteenth gatherings—including Houston’s Emancipation Park, Mexia’s Booker T. Washington Park, and Emancipation Park in Austin."

According to the Handbook of Texas:

'The day has been celebrated through formal thanksgiving ceremonies at which the hymn "Lift Every Voice" furnished the opening. In addition, public entertainment, picnics, and family reunions have often featured dramatic readings, pageants, parades, barbecues, and ball games. Blues festivals have also shaped the Juneteenth remembrance. In Limestone County, celebrants gather for a three-day reunion organized by the Nineteenth of June Organization. Some of the early emancipation festivities were relegated by city authorities to a town's outskirts; in time, however, black groups collected funds to purchase tracts of land for their celebrations, including Juneteenth.

'In the state capital, Juneteenth was first celebrated in 1867 under the direction of the Freedmen's Bureau and became part of the calendar of public events by 1872. Juneteenth in Limestone County has gathered "thousands" to be with families and friends. At one time 30,000 blacks gathered at Booker T. Washington Park, known more popularly as Comanche Crossing, for the event. One of the most important parts of the Limestone celebration is the recollection of family history, both under slavery and since. Another of the state's memorable celebrations of Juneteenth occurred in Brenham, where large, racially mixed crowds witness the annual promenade through town. In Beeville, black, white, and brown residents have also joined together to commemorate the day with barbecue, picnics, and other festivities.

'Juneteenth declined in popularity in the early 1960s, when the civil-rights movement, with its push for integration, diminished interest in the event. In the 1970s African Americans' renewed interest in celebrating their cultural heritage led to the revitalization of the holiday throughout the state. At the end of the decade Representative Al Edwards, an African-American Democrat from Houston, introduced a bill calling for Juneteenth to become a state holiday. The legislature passed the act in 1979, and Governor William P. Clements, Jr., signed it into law. The first state-sponsored Juneteenth celebration took place in 1980.'

I can only imagine the feelings of those hearing this news in 1865. Juneteenth.com states:

"Later attempts to explain this two and a half year delay in the receipt of this important news have yielded several versions that have been handed down through the years. Often told is the story of a messenger who was murdered on his way to Texas with the news of freedom. Another, is that the news was deliberately withheld by the enslavers to maintain the labor force on the plantations. And still another, is that federal troops actually waited for the slave owners to reap the benefits of one last cotton harvest before going to Texas to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation. All or none of them could be true. For whatever the reason, conditions in Texas remained status quo well beyond what was statutory."

My personal guess, as the descendant of Texas slaveowners, that the second and perhaps the third of these explanations is the most likely.

"The reactions to this profound news ranged from pure shock to immediate jubilation. While many lingered to learn of this new employer to employee relationship, many left before these offers were completely off the lips of their former 'masters' - attesting to the varying conditions on the plantations and the realization of freedom. Even with nowhere to go, many felt that leaving the plantation would be their first grasp of freedom. North was a logical destination and for many it represented true freedom, while the desire to reach family members in neighboring states drove some into Louisiana, Arkansas and Oklahoma. Settling into these new areas as free men and women brought on new realities and the challenges of establishing a heretofore non-existent status for black people in America.

"Recounting the memories of that great day in June of 1865 and its festivities would serve as motivation as well as a release from the growing pressures encountered in their new territory. The celebration of June 19th was coined "Juneteenth" and grew with more participation from descendants. The Juneteenth celebration was a time for reassuring each other, for praying and for gathering remaining family members. Juneteenth continued to be highly revered in Texas decades later, with many former slaves and descendants making an annual pilgrimage back to Galveston on this date.

"A range of activities were provided to entertain the masses, many of which continue in tradition today. Rodeos, fishing, barbecuing and baseball are just a few of the typical Juneteenth activities you may witness today. Juneteenth almost always focused on education and self improvement. Thus often guest speakers are brought in and the elders are called upon to recount the events of the past. Prayer services were also a major part of these celebrations.

"Certain foods became popular and subsequently synonymous with Juneteenth celebrations such as strawberry soda-pop. More traditional and just as popular was the barbecuing, through which Juneteenth participants could share in the spirit and aromas that their ancestors - the newly emancipated African Americans, would have experienced during their ceremonies. Hence, the barbecue pit is often established as the center of attention at Juneteenth celebrations.

"Food was abundant because everyone prepared a special dish. Meats such as lamb, pork and beef which not available everyday were brought on this special occasion. A true Juneteenth celebrations left visitors well satisfied and with enough conversation to last until the next.

"Dress was also an important element in early Juneteenth customs and is often still taken seriously, particularly by the direct descendants who can make the connection to this tradition's roots. During slavery there were laws on the books in many areas that prohibited or limited the dressing of the enslaved. During the initial days of the emancipation celebrations, there are accounts of former slaves tossing their ragged garments into the creeks and rivers to adorn clothing taken from the plantations belonging to their former 'masters'." (Juneteenth, Manhattan, Kansas, 1997, photo © Kerry Stuart Coppin)

(Juneteenth, Manhattan, Kansas, 1997, photo © Kerry Stuart Coppin)

Since I prefer to read first-hand accounts rather than the often self-serving synopses of academics and outsiders reporting on a culture or event, I went to the Library of Congress's online source for Slave Narratives gathered by the Federal Writers' Project, 1936-1938. These are organized by the names of former slaves, or by state for the photographs alone. This a wealth of accumulated life stories which tell both the grim reality of life under slavery and, often, a "dey wuz good to us" version that is clearly meant as appeasement to the white interviewer. Both are equally revealing.

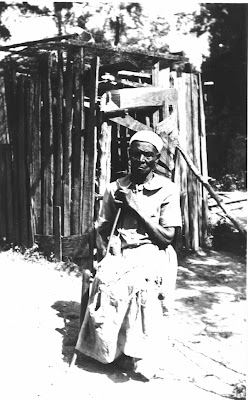

I selected one story with an accompanying photo, the interview with Issabella Boyd, who was brought from Richmond, Virginia to Beaumont, Texas as a little girl with her enslaved parents. She was interviewed between 1936 and 1938, making her at least 80 years old. It's after the fold.

Go have some barbecue and strawberry soda, ya'll. Dance, listen to the stories of those older than you, and celebrate the freedoms we do have, however late they got here. Tomorrow we'll go back to the work of demanding more. (Issabella Boyd, Beaumont, Texas, circa 1936-1938)

(Issabella Boyd, Beaumont, Texas, circa 1936-1938)

Click on images to enlarge. These are the best resolution available.

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

2:18 AM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Issabella Boyd, Juneteenth, racism in US, slavery

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

TWO IMPORTANT STORIES ABOUT AFRICA

(Liberia, filming for Communication for Change, photo by Eve A. Lotter)

(Liberia, filming for Communication for Change, photo by Eve A. Lotter)

The Utne Reader has a good article up, Through Their Eyes, about how refugee women who are assaulted (sexually and otherwise) in West Africa are making videos expressing what it looks like through the eyes of the victims. I'm posting this to encourage you to donate what you can to the non-profits who are sponsoring this project and the community viewings/speak-outs afterward, American Refugee Committee International (ARC) and Communication for Change. Woman-created videos are also being made about forced marriage and wife beating.

But I also want to take this opportunity to comment on the language used in writing this article and how it contributes to dilution of feminism and clear thinking about what is really going on. The tag at the top reads "Victims of gender-based violence fight back with video" and the lead-in states "The crime is all too familiar for many women and girls around the world, especially those living in refugee camps where gender-based violence has become endemic: Rape is a weapon of war, forced sex a currency exchanged for food or safe passage."

But this is not, strictly speaking, gender-based violence. It's woman-hating. It's ONLY aimed against women and girls, not against a generic "gender". I mean, the corollary would be to sanitize lynching by referring to it as "race-based violence" instead of community murder of black people.

I believe this semantic shift is underway to make discussion of crimes against WOMEN somehow more palatable to the mainstream, less feminist and more "gender-studies" friendly: For all those who have difficulty facing the fact that sexism is second-class status and hatred of WOMEN AND GIRLS (and anyone else who can incidentally be shoe-horned into the NOT-MAN category.) "Gender-based" should be reserved for those statistically rare instances when the oppression is clearly being aimed against all "not-men", instead of specifically targeting women and girls. The conflation of terms does no justice to the different expression of oppressions as it is experienced by different targets. Those of us in the belly of the beast deserve to not have our struggles lumped together into academically polished and distancing language.

Recommended reading: Rape in Liberia at Womanist Musings (From the Middle Passage drawings by Tom Feeling)

(From the Middle Passage drawings by Tom Feeling)

A couple of weeks ago, there was a fascinating article in the Boston Globe online about new research from a Harvard economist which "suggests that Africa's economic woes may have their roots in the slave trade" (hat tip to Jesse Wendel of Group News Blog for sending this my way). This is not an original idea -- the theory has been around for a long time. But Nathan Nunn has created innovative (and still untested) measures to verify his argument "that the African countries with the biggest slave exports are by and large the countries with the lowest incomes now (based on per capita gross domestic product in 2000). That relationship, he contends, is no coincidence. One actually helped to cause the other."

The article, Shackled To The Past, by Francie Latour, is detailed enough that you need to go read it yourself.

However, I want to address a couple of ideas within it. One section reads:

"Nunn's research also comes at a time when the most fervent calls for reparations have come and gone, but when international calls for Western apologies for slavery still draw attention. The United States has never apologized for slavery, although five states - Virginia, Maryland, Alabama, North Carolina, and New Jersey - have done so recently, and Congress is poised to consider a resolution of apology this year. With much of the world's trade policy heavily skewed to the West's advantage and Africa's disadvantage, some say apologies carry little if any value. In any case, it remains to be seen whether the United States will ever face the role it played in one of history's worst crimes."

...

"The echoes across time are fascinating, and seem undeniable. But many practitioners say that ultimately, looking at Africa's problems through the lens of slavery is self-defeating. Calestous Juma, a native of Kenya and one of the most influential voices on African economic development, falls squarely into this camp.

'The legacy of slavery cannot be denied, but if you push the argument too far, it becomes a fatalistic argument," said Juma, a professor at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government. 'Because you start to say, "Well, what can we really do? We can't undo the past, and therefore, Africa will always remain poor."'

I've thought about the idea of reparations and apology from different angles for decades now. In the 1980s, I dated a woman who was active in the African People's Socialist Party. Their platform then, and now, included reparations for African slavery in this country. While I was behind it in principle (and, I have to say, most of the other planks in their platform), I didn't think it was a realistic demand and that its quality of being "far-fetched" would detract from the other goals they were pursuing.

I've changed my mind since then. To begin with, the labeling of a goal as "far-fetched" is always soaked in cultural and target versus non-target group assumptions. Given my radicalism on so many other issues, I think it's safe to say my willingness to see reparations as "out there" arose from racism more than sudden rationality.

To illustrate my point, other reparations movements (such as Jews claiming damages from the Holocaust) meet with far more public (i.e., white people) acceptance and respectful airplay. However, the turd in the punchbowl is that the wealth of the United States is utterly founded on theft of land and labor. There is a prevailing myth to the contrary, especially among white people, that America's "greatness" is the product of hard labor. Labor by men, this means. White men. The work of women is taken for granted, and the resources of others is considered the property of white men by manifest destiny and Christian-backed racial superiority.

Relinquishing this myth to reality would do more than flood the foundations of white supremacy and woman-hating. It would also remove the chief delusion propping up white working class compliance with rule by the power elite: The fantasy that their own hard work will lead to class advancement and stability. Forcing the white lower classes in this country to face the truth that their status, however shitty, is never going to change through their own efforts and, even so, they are advantaged in comparison to the people of color living around them would lead to revolution.

If we took a zen approach to undoing the past -- we can't really time travel, but we can undo the effects of the past manifested present-day -- we'd have enormous opportunity to level economic prosperity on a global level. Since America currently stands squarely in the past of this progress, anything which would address the cultural and psychological pathology supporting such obstruction could help jiggle it loose.

For this second-tier reason, then, I'm also in favor of pushing for reparations. Bringing the actual source of our economic advantage into the clear light of day would be immensely tonic for my class, and enable us to (possibly) step around the racism which keeps us doing the dirty work of standing on our sisters' and brother's necks. I can only hope.

Likewise, governmental apologies have been applauded by everyone except Republicans and their ilk. In its honest form, an apology says "I see what I did there, I feel badly for how my action hurt you, and I'm going to take steps to make sure I don't do it again." Apology is an adult skill, arising from a blend of developmental attainment and responsibility -- to others AND to self. Which explains why it is beyond the reach or comprehension of conservatives and evangelicals, but we have to not let their limitations be our lowest common denominator any longer.

The article states:

"Juma and Nunn may be working toward an eventual meeting of the minds. The Kenyan sees slavery's lasting scar as a deeply psychological one - an attack on the self-confidence of a continent, and by extension, its human potential. Until that legacy is conquered, Juma said, Africa will not advance.

"Nunn, now at work on Chapter 2, has another name for this legacy: He calls it the trust channel. He can't prove it. But using household surveys of Africans over the last seven years known as the Afrobarometer, he is finding that ethnic groups that had the most slaves taken in the past express the most difficulty trusting people within their group, and outside their group. It may be that as it ravaged populations and crippled institutions, the hunting down and handing over of their own kin also robbed them of an innate ability to trust, all the way to the present day.

"Measuring this kind of collective feeling, and correlating it to events so far in the past, will likely put Nunn right back on slippery ground. But he doesn't seem to mind. 'The idea of the transmission or evolution of trust over generations, and this being affected by these large historic events,' Nunn said, 'is definitely not mainstream in economics.'"

I was fascinated by the introduction of this word, trust. (As was Jesse, hence his recommendation to read this article.) Trust of course arises from relationship, and dysfunctional/damaging relationships erode trust backwards and forwards along the temporal plane. I think it is possible that this is perpetuated not just through conditioning and culture -- i.e., we raise our children to distrust because of a devastating betrayal in the past. I think it is possible that this erosion of trust is making its way into biological expression via epigenetics: The way in which rearing and environment (nurture) alters our very biology, either temporarily (during our lifetime) or in a more long-lasting fashion (altering the genes that get passed on).

The plasticity of our genetic expression as is currently being discovered, daily, through epigenetic study is where the hope lies in this revelation of centuries of distrust. It's a reversible condition.

But apology will be the first step in that healing. There's no way around it. It will be good for us, good for the world, good for future generations. When you write your elected representatives or speak to the powerful, I ask to you add this to your list of requests: That we learn how to apologize, and do it (on every scale) when we have transgressed. It's not enough to sing "Amazing Grace" any more (as if it ever was), marveling at that which "saved a wretch like me" but not moving emotionally to the next step. We have to reverse the Middle Passage, in whatever ways we can dream up. Wouldn't you rather live in a world which took on this task?

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

9:28 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Africa, apology, APSP, ARC, classism, Communication For Change, epigenetics, feminism, gender studies, Nathan Nunn, racism, rape, reparations, slavery, woman-hating

Saturday, March 8, 2008

ON INTERNATIONAL WOMEN'S DAY

(Harriet Tubman, photo by James A. Gensheimer)

(Harriet Tubman, photo by James A. Gensheimer)

I like to think of Harriet Tubman. (hat tip to Susan Griffin*)

I was thinking about her as I woke up today. I often see her referred to as "the Moses of her people". Well, if Moses had returned to Egypt 19 times over ten years to rescue more of his people, if he had grown up beaten (disabled from one blow) and starved instead of as a foster brother to the Pharaoh, if he had received no divine assistance when being pursued by those who would kill him -- then yeah, she'd be like Moses. The truth is, her personal courage and intelligence exceeds that of most other American heroes.

Why don't we hear as much about her as Malcolm X or W.E.B. Dubois? Here's a question for you: How much more attention would she get if she'd been a man?

We know what happened to the people that Moses led from slavery. Thanks to his actions, the world has known the likes of Sigmund Freud, Paula Abdul, Albert Einstein, Stan Lee, Carole King, Jonas Salk, Nadine Gordimer, George Gershwin, k.d. lang, Louis Brandeis, Katharine Graham, Karl Marx, Anne Frank, Allen Ginsberg, Levi Strauss, Frida Kahlo, Leonardo da Vinci, Andrea Dworkin, the motion picture, comedy and garment industries, and, oh yeah, Jesus.

Who are the descendants of those Harriet Tubman saved? Why don't we know their names, too? (Harriet Tubman, far left, standing with a group of slaves whose escape she assisted)

(Harriet Tubman, far left, standing with a group of slaves whose escape she assisted)

She carried scars. She was put to work at around five or six. When she was 12, she began work in the fields. At around this time, she blocked a doorway to protect another field hand from an angry overseer. The overseer threw a two-pound weight at the field hand, but it struck Harriet on her head, leaving her with a condition like narcolepsy.

But she never lost a person in her rescue journeys. She was endlessly inventive. You should know all about her, go read about her. She worked as a spy for the Union during the Civil War, as well as a cook and a nurse. In later years, she fought for women's rights, and founded a home for the aged and infirm which still stands today. But she was denied a military pension, despite having led African-American soldiers on raids along the Combahee River in South Carolina in 1863.

White people tend to believe that slaves were kept in bondage, in part, by fear of beatings and reprisal. We are also told that ending slavery was the reason why the North fought the Civil War, and that blacks were rescued by whites. None of these things are literally true, and it serves to maintain the myth of white supremacy, of African-Americans as helpless.

When physical violence was used on plantations, the African-Americans there were more likely to run away, to destroy profit, to use all the means at their disposal to make life wretched for the whites who abused them. Of course. It has been argued, convincingly I find, that the purpose of beatings and overt acts of violence was not to "keep the slaves in line" but rather to reinforce the numbness of the whites -- to add on layers of brutality to their psyches, so they would remain in their role as slaveowners despite the obvious, daily humanity of the people they owned.

That's the way oppression works. Create a lie to cover the real reason for subjugation, and repeat it in every cultural manner available, including the use of force, to keep both sides separated.

A woman dares run for President? Woman-hating comes out from under whatever wraps it might have (barely) worn. We know what Hillary Clinton has endured for a couple of decades. We know how tough she is, and what scars she carries. She's flawed, no doubt about it, and damaged from what she's gone through. She's no FDR. But neither is Barack Obama. He's not Harriet Tubman. And while he's just as assuredly flawed, we don't know the extent of his damage yet. If elected, he WILL disappoint us. If he weren't being compared to Bush, I think we'd be able to be more realistic about him.

Those of us old enough to remember the Nixon era can remember the shock we all felt when we discovered he kept an "enemies list". It was unheard of, then. Of course politicians opposed one another, and different factions worked to undo each other's goals. But Nixon labeled those who disagreed with him "enemies" and sought to use any means available to destroy their lives. It was a window into a secret world. It could have been a great lesson, a chance to admit American use of power (the role of overseers, for example) and change.

Real change means naming the problem and insisting on either reform of those who abuse humanity or removing them from a position where they can do harm. We're approaching another such reckoning day here in this country. I hear people's fears that our Congress will not enforce change. They want a President who will lead the way to cleaning house. They point to Clinton as a moderate, an insider who will not go far enough. I can't argue. But I see no evidence at all that Obama will, either. He's already turned belly up on the issue of gay rights.

What else is new. He's moderate as well, not a thoroughbred liberal.

I think it's important to remember the typical human response to bullying, to punishment, and to torture: We do whatever is asked of us until we feel free from threat, but we do not actually change or grow. This week Canada has informed us they will not be using any information obtained by our CIA, since it is tainted from being obtained by torture and is therefore worthless.

Molly Ivins, and others, in 2000 warned the country that Dubya was vindictive -- that if he did not get his way, he (and his crew) set about punishing those who disagreed with him, in illegal and unparalleled fashion. He's had our government in a reign of terror since. We now have a Congress infected with this fear. Two of its Senators (well, three if you count McCain, but I don't) are now running for President. None of them have pushed for impeachment. None of them have actually bucked the status quo. Cleaning house is going to take longer than the made-for-TV version.

We'll have to wait for our Harriet Tubman.

Happy International Women's Day.

*I LIKE TO THINK OF HARRIET TUBMAN

(copyright Susan Griffin, from her book Like the Iris of an Eye, published by Harper and Row, New York)

I like to think of Harriet Tubman.

Harriet Tubman who carried a revolver,

who had a scar on her head from a rock thrown

by a slave-master (because she

talked back), and who

had a ransom on her head

of thousands of dollars and who

was never caught, and who

had no use for the law

when the law was wrong,

who defied the law. I like

to think of her.

I like to think of her especially

when I think of the problem

of feeding children.

The legal answer

to the problem of feeding children

is ten free lunches every month,

being equal, in the child's real life,

to eating lunch every other day.

Monday but not Tuesday.

I like to think of the President

eating lunch on Monday, but not

Tuesday.

And when I think of the President

and the law, and the problem of

feeding children, I like to

think of Harriet Tubman

and her revolver.

And then sometimes

I think of the President

and other men,

men who practice the law,

who revere the law,

who make the law,

who enforce the law

who live behind

and operate through

and feed themselves

at the expense of

starving children

because of the law.

Men who sit in paneled offices

and think about vacations

and tell women

whose care it is

to feed children

not to be hysterical

not to be hysterical as in the word

hysterikos, the Greek for

womb suffering,

not to suffer in their

wombs,

not to care,

not to bother the men

because they want to think

of other things

and do not want

to take women seriously.

I want them to think about Harriet Tubman,

and remember,

remember she was beaten by a white man

and she lived

and she lived to redress her grievances,

and she lived in swamps

and wore the clothes of a man

bringing hundreds of fugitives from

slavery, and was never caught,

and led an army,

and won a battle,

and defied the laws

because the laws were wrong, I want men

to take us seriously.

I am tired of wanting them to think

about right and wrong.

I want them to fear.

I want them to feel fear now I want them

to know

that there is always a time

there is always a time to make right

what is wrong,

there is always a time

for retribution

and that time

is beginning.

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

6:42 PM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Barack Obama, Harriet Tubman, Hillary Clinton, Moses, resistance, slavery, Susan Griffin

Monday, March 3, 2008

PORTRAYING AMERICAN SLAVERY

(Broadside, dated Charleston, 24 November 1860. Courtesy of the Gilder Lehrman Collection, Pierpont Morgan Library)

(Broadside, dated Charleston, 24 November 1860. Courtesy of the Gilder Lehrman Collection, Pierpont Morgan Library)

The newly online website Common-Place, sponsored by the American Antiquarian Society in association with the Florida State University Department of History, has a treasure trove of previously published articles now available for the self-directed reader of history. I'll be recommending several gems in posts to come. I'm beginning with a series of articles published in July 2001, entitled Representing Slavery: A Roundtable Discussion.

I especially recommend the essay by A.J. Verdelle, The Truth of the Picnic: Writing about American slavery. Her bio here states "A. J. Verdelle is the author of The Good Negress (Chapel Hill, 1995), for which she was awarded a Whiting Writer's Award, a Bunting Fellowship at Harvard University, a PEN/Faulkner Finalist's Award, and an award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters for distinguished prose fiction."

In her stunningly relevant essay, Verdelle states "Slavery and its aftermath are human drama still unsettled. Administrators, timekeepers, civil servants, guardians of the state try to revise our understanding of the period and its outcomes. An effort to convince us that the drama is over rages. Some of us insist, and rightly so, that we are now in this drama's second act, we have not moved beyond the raised curtain, we are still in shock at what we have finally seen."

Also in the Representing Slavery roundtable discussion are the following essays:

Confronting Slavery Face-to-Face: A twenty-first century interpreter's perspective on eighteenth-century slavery", by Karen Sutton, a historical interpreter in the African-American Programs & History Department, Division of Historic Presentations, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

The Birth of a Genre: Slavery on film, by David W. Blight, who teaches history and black studies at Amherst College. He is the author of Frederick Douglass' Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee (Baton Rouge, 1989), and Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, Mass., 2001). He has been a consultant to several documentary films, including the PBS series Africans in America (1998).

Seeing Slavery: How paintings make words look different, by Alex Bontemps, who teaches African American history at Dartmouth College. His book, The Punished Self: Surviving Slavery in the Colonial South (Ithaca, N.Y., 2001), was recently published by Cornell University Press.

Hearing Slavery: Recovering the role of sound in African American slave culture, by Shane White and Graham White. Shane White is an associate professor and Graham White an honorary associate in the history department at the University of Sydney. Together they have written Stylin': African American Expressive Culture From Its Beginnings to the Zoot Suit (Ithaca: 1998) and have half completed The Sounds of Slavery, which will be a book and a twenty-four-track CD.

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

12:32 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: A.J. Verdelle, Common-Place, slavery

Thursday, February 7, 2008

ALABAMA WHITE/BLACK GENEALOGY

From the time of the American Revolution until 1818, what was known as the Mississippi Territory (today's states of Mississippi and Alabama) was variously controlled by France, Spain, Great Britain and several Indian nations, particularly Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Cherokee. To travel beyond Georgia, U.S. citizens had to obtain a passport from whichever nation held the territory they were crossing.

However, the U.S. relentlessly used every means at its disposal to make this territory their own, and by 1820, both Mississippi and Alabama had been largely stolen from its Native peoples and was being opened to white expansion. My Armstrong, Randolph, Ussery and Fuller ancestors from the Scots enclaves around Montgomery Co., North Carolina relocated westward, first going to Monroe County, Mississippi (on the border with northwestern Alabama), then obtaining land grants in the watershed of Bear Creek, Chickasaw Nation, what is now Franklin and Marion Counties, Alabama.

They were the first white people to live on the lands they received. As best I can determine, the people they displaced were Chickasaw, who had attempted to adopt European agriculture and treat peacefully with the U.S. -- fat lot of good it did them, not with Andrew Jackson in the White House. My Scots forebears hated governmental interference except when it stole other people's land and gave it to them.

My ancestors, like most of the whites pouring in, were fleeing soil they had exhausted by the over-cultivation of cotton. They obtained rich land of the Black Belt and Tennessee Valley. With them they brought slave labor and the plantation system, though on a smaller scale than the Delta region. During the first half of the 1800s, a steady demand for cotton made this the U.S.'s leading export.

I cannot find a record of my direct ancestors owning slaves in Mississippi or Alabama. They were cotton farmers, but also seemed to raise horses for income. By 1860, my main lines migrated northwest to Sharp County, Arkansas, where they did not own slaves, either. This is where they were at the time of the Civil War and where every male between the age of 14 and 55 served in the CSA.

I'm currently working on an intensively researched essay about my Confederate ancestry, trying to puzzle out where my family's CSA service is typical or unusual and how that might have handed down current family values. In the meantime, I turned to this one branch of interrelated families today because I've been writing a section of my novel Ginny Bates that has to do with the ancestry of Allie Billups, an African-American lesbian character whom I located as having grown up in the Franklin/Marion County, Alabama region. I'm looting my own family background (where it applies across racial lines) and knowledge of the area to create a back-story for Allie.

Last night, Henry Louis Gates Jr. (a pre-eminent African-American historian and genealogist) aired the second installment of his African-American Lives epic on PBS. I was riveted, again, and realized the history of the Great Migration needed to be in Allie's story as well.

At the taking of the U.S. Census in 1860, Franklin County, Alabama was 45% African-American (of which all but 13 were slaves) and 55% European-American. Currently, however, Franklin County is about 90% white, 4% black, and 5% Latino. The average for Alabama is 71% white, 26% black, which means Franklin County is off skew.  (Slave quarter from Belmont Plantation, Colbert Co. AL which was formed from Franklin Co. AL, 1936, taken by Alex Bush; from Back of the Big House: Cultural Landscape of the Plantation)

(Slave quarter from Belmont Plantation, Colbert Co. AL which was formed from Franklin Co. AL, 1936, taken by Alex Bush; from Back of the Big House: Cultural Landscape of the Plantation)

One African-American genealogy site states "Subject to the effect of the formation of Colbert County from the northern part of Franklin in 1869, by the 1870 census, the white population of Franklin County had decreased almost 34% to 6,693, while the "colored" population decreased over 84% to 1,313. (As a side note, by 1960, 100 years later, the County was listed as having 20,756 whites, about twice as many, but the 1960 total of 1,231 "Negroes"was only about one seventh of what the colored population had been 100 years before.) Where did all the freed slaves go, that were not in Franklin or Colbert County in 1870? Dallas, Montgomery and Mobile counties in Alabama all saw increases in the colored population between 1860 and 1870, so that could be where some of these freed slaves went. Between 1860 and 1870, the Alabama colored population increased by 37,000, to 475,000, a 17% increase. Between 1860 and 1870, the Alabama colored population increased by 37,000, to 475,000, a 17% increase. Where did freed slaves go if they did not stay in Alabama? States that saw significant increases in colored population during that time, and were therefore more likely possible places of relocation for colored persons from Franklin County, included the following: Georgia, up 80,000 to 545,000 (17%); Texas, up 70,000 (38%); North Carolina, up 31,000 (8%); Florida, up 27,000 (41%); Ohio, up 26,000 (70%); Indiana, up 25,000 (127%); and Kansas up from 265 to 17,000 (6,400%)."

I haven't yet done the research to trace this demographic, or to discover the particular effects of the Great Migration on Franklin County during 1900-1930, when blacks fled the South for Northern cities in the largest movement of people this country has seen. However, I am keeping in mind the bigger idea, which is that if black people chose to abandon Franklin County in huge numbers as soon as they were emancipated, their living conditions there were worse than other counties in the South. As Gates' program indicated, with no money, no skills except farming, and no region seeking them, newly-freed slaves were overwhelmingly sucked back into the near-slavery of sharecropping by the time Reconstruction had been betrayed by the Republican Party. Yet Franklin County blacks, in particular, opted to share-crop elsewhere no matter the rigors of relocating. (Laura Clark, former slave from Sumter County, Alabama, photograph possibly by Ruby Pickens Tartt, ca. 1938, from Back of the Big House: Cultural Landscape of the Plantation)

(Laura Clark, former slave from Sumter County, Alabama, photograph possibly by Ruby Pickens Tartt, ca. 1938, from Back of the Big House: Cultural Landscape of the Plantation)

In 1985, I went to Franklin and Marion Counties as part of a general genealogy research trip across the South. Of all the places I visited, it was the one place where I felt frightened for my safety as a lesbian and as a woman traveling with other women (not necessarily the same thing). There was no friendliness to strangers to be found by me and my companions, despite my accent and our serious attempts at charm. The poverty was strong, but other equally poor places still had people who would talk to us. I located the land where my ancestors had farmed -- a neighboring tract even had a still-standing dog-run log cabin from the early 1800s on it -- and when I walked the clay soil, what came to me was not my people reaching out over time (which often happened to me on these trips) but desolation. (Helen Keller and Annie Sullivan)

(Helen Keller and Annie Sullivan)

We arrived there after having the day before visited Ivy Green, the home of Helen Keller, now a museum filled with photos of her life with Annie Sullivan. In the back yard was the famous well and pump. I had been overjoyed to see it, to claim a woman-loving connection with this extraordinary leader. From there, we'd gone to the Coon Dog Memorial Cemetery near Tuscumbia, Alabama, another place which had moved us deeply with its headstones, often primitive, extolling the love of men for their dogs. Thus, I was taken off utterly off guard by the depression I felt in Franklin County.  (The pump at Ivy Green where Helen Keller learned the word for water)

(The pump at Ivy Green where Helen Keller learned the word for water)

Something is there to be uncovered. Since my ancestors were on the white side of that equation, I want to know why. I'll keep you informed.

In the meantime, do whatever you can to catch your PBS station's viewing of African-American Lives. Family histories this time include those of Tina Turner, Jackie Joyner-Kersee, Don Cheadle, Chris Rock, Maya Angelou, Morgan Freeman, and six others. It's better than the first go round in 2006. There'll be an additional two hours' shown next week as well. The website has an incredible timeline and set of sources. Gates' is permanently affecting the lives of those folks whose ancestry he traces (he made Chris Rock weep with one discovery) but also rewriting American history in a manner we've ardently needed. Watch it.

RESOURCES FOR FRANKLIN CO., ALABAMA:

Genealogy for Franklin Co., AL

African-American genealogy for Franklin Co., AL

Native American genealogy for Franklin Co., AL

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

4:32 PM

7

comments

![]()

Labels: African-American Lives, Chickasaws, Franklin Co. AL, Great Migration, Helen Keller, Marion Co. AL, slavery

Tuesday, February 5, 2008

ABDUL RAHMAN IBRAHIM IBN SORI

(Drawing of Abdulrahman Ibrahim Ibn Sori)

(Drawing of Abdulrahman Ibrahim Ibn Sori)

Several years ago I had the opportunity to compile a genealogy for a friend who is a nationally-respected African-American writer. This led me inevitably to slave genealogy, primarily in the Mississippi Delta region, and it was during the course of reading everything I could on the subject that I can across the story of Abdul Rahman: The only African stolen from that continent, made a slave here, who was able to return to Africa and write about the experience of slavery. A singular voice.

I was so rocked by Abdul Rahman's story that I wrote a poem about it. I later learned about the book Prince Among Slaves by history professor Terry Alford, chronicling his life. Now Unity Productions Foundation has created an award-winning documentary based on Alford's book (and narrated by Mos Def) which was aired on PBS last night. Check your local PBS listings; since this is Black History Month, you may well have a chance to see it in your area, and you should make every effort to watch it if you can.

Here's the (sketchy) Wikipedia entry on Abdul Rahman. A much better biography is available at the Slavery in America site. The Unity Productions Foundation about the film is here. (I was particularly interested in the genealogy leads at the latter site.)

My poem is after the fold.

ABDULRAHMAN IBRAHIM IBN SORI

He was a Fulbe prince. He could read and write

With these in hand we sketch the arc, the why:

Of all those who made the Middle Passage

And survived -- already select, hardy, smart, lucky --

He alone found the way back home

And then, o bless you Ibrahim

Set ink on paper to tell us

What he felt

The brutality, we've learned

The mechanics of it, the rot

We have imagined

But here is his voice, clearer than god

Saying it was the unimaginable

That threatened him most

He, like his folk, knew slavery

as stolen labor -- Crime enough

yet a crime with exit hatches

But these new ones, some kind of maybe-people

They stole entire humanity

He, like his folk, believed these thieves

must be cannibals -- how else to explain

the absence of return, ever

They must consume the stolen

down to marrow cracked from bones

So when he was in the wrong place,

At the only time he had -- his own --

And fell into the hands of such savages

He prepared for death

Waited for the knife

Waited while chained in dark sewers

Taken to a place not on any map

His offers of ransom were not honored

Or even comprehended.

He was set to hoeing cotton.

Not to die -- at least not die

Direct. But the work, hunger, beatings

Were not what kept him from

The living. It was the

Not Knowing

Not knowing where he was or any route

Back to his kind of people

Not knowing how it was he could fail

To be seen as likewise human

One day he reached decision

Set down his hoe and walked steady

Toward the woman of the two

Who believed they owned him

She faltered at his approach, turned

For weapon or flight. But he

Knelt before her, pressed his forehead

Into Mississippi dirt, and

Gently lifted her foot

To place it on his neck

In his true language, he swore fealty

Swore his honor

She didn't understand, not the real of it

But he did. And this settled his torture

Later, incredibly,

He was recognized by a traveler

Named

Freed

Bought free his wife

And sailed back home

The only one of his kind

If you still cling to your confusion

Find a greater comfort there

Cannot hear all of what our people did

Cannot accept it without excuse

Or even refuge of guilt

If you want to believe it is over, now --

Your own preferences are accidental, innocent --

I will not wrangle

But I do hector you with this:

Understand his honor His choice

Understand how he clenched his power

By saying it was his to give

Understand that

And your road opens

Copyright 2008 Maggie Jochild, written 2 October 2003, 5:05 p.m.

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

1:15 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Abdul Rahman, Prince Among Slaves, slavery, Terry Alford

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

REFLECTING

My great-aunt Lee did not care much for Thanksgiving. She observed it, because there seemed to be no real alternative, but she took pains to point out that it was a "Yankee" holiday, imposed on the country during the Civil War when the actual founding colony of America, Jamestown, could be ignored. As a child, I was taken aback by her pronouncements, just as I was shocked when she showed no approval for my having memorized the Gettysburg Address: She said I could find far more admirable language to commit to memory than that of "Mr. Lincoln", a President whose virtues she felt were grossly overstated.

She certainly knew her history. She and my great-uncle John Thomas spent countless summers as re-enactors at Colonial Williamsburg, residing in the Berkeley House in authentic pre-revolutionary style. They were both teachers of history and English, in public schools and colleges. They were instrumental in getting the Texas State Archives founded here in Austin. Aunt Lee is the source of our voluminous, impeccably documented genealogy, remarkable in a family line of poorly-schooled subsistence farmers. She was ferociously supportive of higher education for women, and she saw no schism between Darwinism and faith in an almighty Creator -- she had no difficulty believing in both, and scorned those who did have trouble. And -- she and Uncle John were John Birchers who longed for a return to an era when "blacks knew their place." Her given name was that of her hero, General Lee.

I loved her very much, contradictions and all. Having to sort through this love has been very good for me, enabling me to be much more successful as an anti-racist activist dealing with my own people.

And, I suspect Aunt Lee was right about the political mythmaking behind Thanksgiving's origins. According to Wikipedia, "On December 4, 1619, a group of 38 English settlers arrived at Berkeley Hundred, comprised of about eight thousand acres (32 km²) on the north bank of the James River near Herring Creek in an area then known as Charles Cittie (sic) about 20 miles upstream from Jamestown, where the first permanent settlement of the Colony of Virginia was established on May 14, 1607. The group's charter required that the day of arrival be observed yearly as a "day of thanksgiving" to God. On that first day, Captain John Woodleaf held the service of thanksgiving." However, "During the Indian Massacre of 1622, nine of the settlers at Berkeley Hundred were killed, as well as about a third of the entire population of the Virginia Colony. The Berkeley Hundred site and other other outlying locations were abandoned as the colonists withdrew to Jamestown and other more secure points."

My first white ancestor in North America arrived at Jamestown in 1609, Captain James Davis. What occurred at Jamestown and its environs over the next few decades is, I think, more essential to establishing the character of the futured United States (and offering object lessons about the problems we've still not addressed) than the 1621 colony of Plymouth Plantation in New England. But the New England version makes for a prettier story, with a hint of nobility about it if you ignore some details, and certainly the Civil War era marks a period of extreme anti-Southern public relations, most of which have economic reasons rather than a sincere moral antipathy toward slavery on the part of the industrial North.

In addition to James Davis, a Cavalier, I also have ancestors from the Camp, Carter, Randolph and Tarpley lines, names familiar to those who study colonial Virginia and especially the James River region. However, these enter my genealogy from another source, not the line that was shared by Aunt Lee. And they are in the minority. Most of my forebears, like hers, were indentured servants, Scots renegades of the class referred to by Sir William Berkeley (of Berkeley House and Plantation connections) when he said "I thank God, there are no free schools, nor printing; and I hope we shall not have, these hundred years; for learning has brought disobedience, and heresy, and sects into the world, and printing has divulged them, and libels against the best government. God keep us from both."

America likes the notion that we were founded by hard-working folks seeking liberty, especially freedom from religious persecution, who came here and transformed a virgin wilderness into the richest nation on earth. We give thanks to this myth every November, and the voices who keep pointing out how very off plumb it is are considered killjoys.

Well, I come from a long line of killjoys. Here's the basics:

---The first settlers were funded by capitalists who expected to make a profit from these ventures, pure and simple. The push to find means of income, not just survival, scarred the early colonies deeply.

---Earlier European contact had introduced diseases which decimated many Native populations, and they were still reeling from this assault, emotionally and practically, when British Isles folks appeared. If tribes had been in their normal state, it seems unlikely any colony would have survived -- the land was simply not "available" for the taking, no matter what religious beliefs the colonists held.

---Colonists who came seeking "religious freedom" were in the minority and did not want freedom in the sense that we understand it -- rather, they wanted to impose their own religious doctrine on their communities. (Sound familiar?)

---If your ancestor came during the 1600s, the odds are greater than half that s/he was an indentured servant. The practice of indentured servitude was violent, destructive to family life, and set the cultural stage for the advanced, most vicious forms of slavery which survived in America far later than in other parts of the industrializing world.

Thus, class divisions between the early colonists were profound and had extreme outcome on survival. If you don't understand the details of this, you will be baffled as to why so many former indentured servants would jump at the chance of introducing African slavery even though they understood its evil.

A couple of years ago, PBS had one of its re-enactment series, Colonial House, wherein a group of ordinary people were trained in the details of life as it was in a 1600s New England colony and set down in a re-created village for six weeks, with cameras recording what transpired. For me, the most riveting outcome was the personal journey of Danny Tisdale, a progressive black man from New York, publisher of Harlem World magazine, who came to the "colony" in the role of a free man of color. Despite tremendous concessions to modern sensibililties, life there turned out to be so arduous, day to day, that at one point this highly intelligent man realized if the option of buying slaves sailed into the nearby cove, he would be tempted. This revelation was so painful, he left the experiment early, unable to resolve the internal crisis it presented.

I know we're currently in a period where Big Lies are the norm, and fundamentalist nuttiness is deliberately seeking to taint all history and science we've ever taken for granted. But the best antidote to dishonesty is, as always, honesty. Educate yourself: An excellent place to start would be to read Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America by Brandeis history professor David Hackett Fischer and/or read the extraordinary essays about this book (three so far, fourth yet to come) by Sara Robinson at Orcinus. Give thanks for what makes sense to you, resist the urge to buy and spend, and love your imperfect beloveds as best you can. Forgive the wretches who populate your family tree even as you make sure you are not a chip off their block. A good life lasts for generations.

Posted by

Maggie Jochild

at

11:34 PM

4

comments

![]()

Labels: Albion's Seed, class inequality, Colonial House, indentured servants, Jamestown, slavery, Williamsburg